Did you know that we can see surface detail on Mars with even a small telescope?

During most of October, Mars rises at sunset and sets at sunrise. It is now (after the sun and moon) the brightest object in the sky and noticeably pinkish!

Mars’ orbit is somewhat elliptical (egg-shaped), meaning that about every two years or so, Mars comes closer to the Earth, becoming both brighter and larger in visual appearance if looking through a telescope.

Some of these close approaches are better than others. This year, on October 6, Mars is closer to us than it will be for the next 15 years, so get out and do some planet-gazing in the autumn air!

The Martian landscape

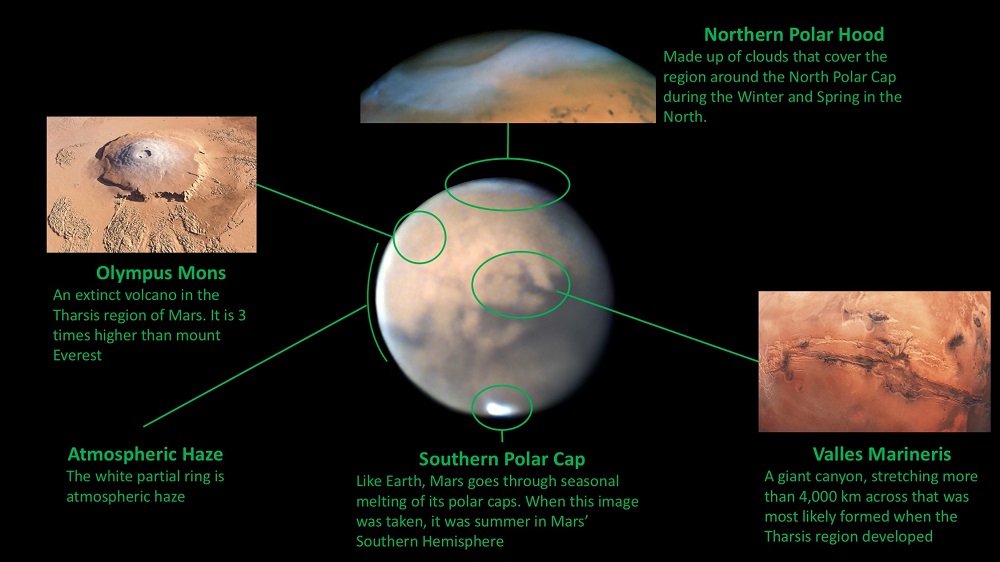

Mars has a number of interesting features including polar caps, massive volcanoes and an incredibly large canyon.

While much smaller than the Earth, Mars goes through seasons due to the tilt of its axis of rotation (similar to Earth’s). This means that Mars’ two polar caps grow and shrink in response to the warmer or cooler weather in that hemisphere.

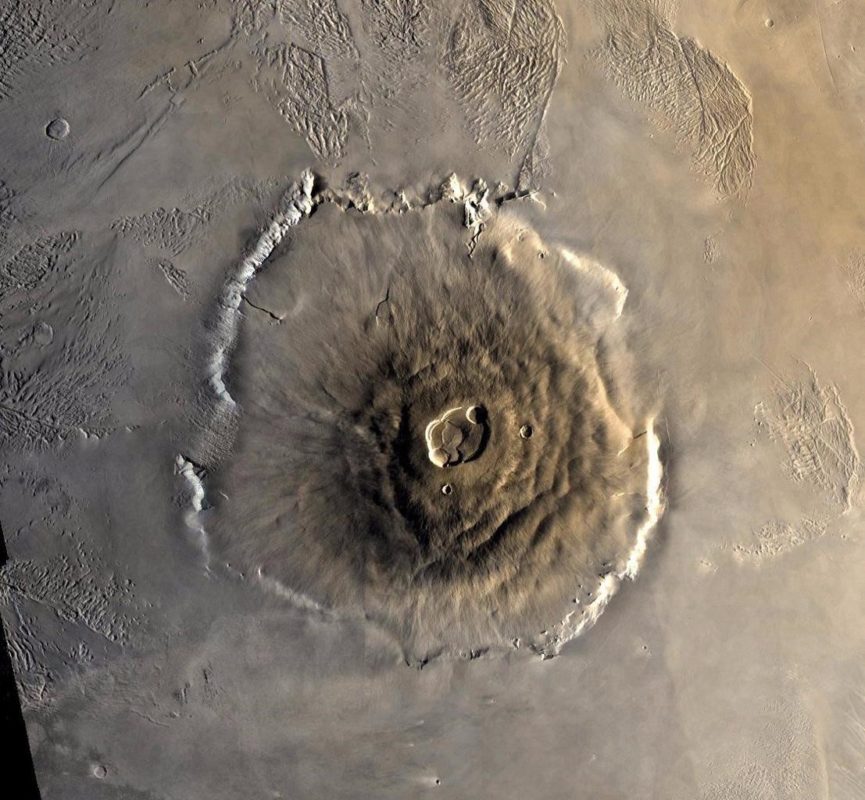

While inactive today, Mars has a number of very large volcanoes. Olympus Mons, the largest volcano, is almost three times higher than Mount Everest and about 400 km across (roughly the distance from Ottawa to Toronto!).

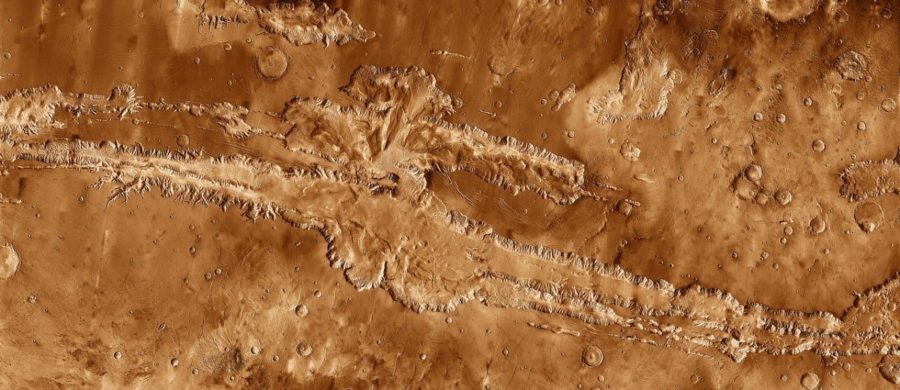

Mars has the most extensive canyon/valley system that we have seen on any object within our solar system. Known as Valles Marineris or Mariner’s Valley (named after the space probe — Mariner 9 — that discovered it), this canyon stretches over 4,000 km across the planet’s surface. The Grand Canyon would disappear into one of the small tributaries in the bottom left of the image below.

Looking at Mars

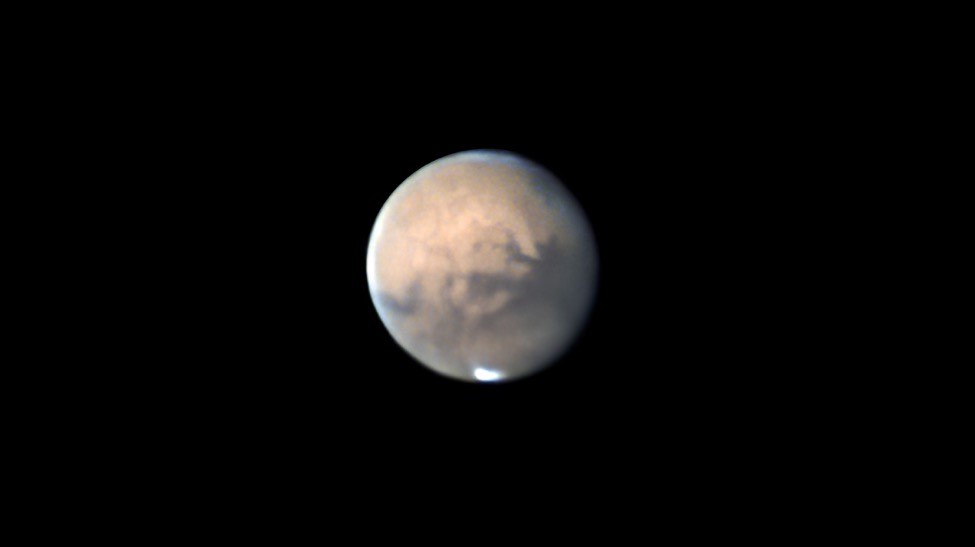

The previous three images were all taken by spacecraft visiting the planet, and are not what one would see in a telescope.

Through a small to mid-sized earth-based telescopes — such as the 16” telescope in the Kchi Waasa Debaabing (Anishinaabemowin for “seeing very far”) Observatory at Killarney Provincial Park — the view is quite different, but interesting nonetheless.

Today, astronomers use a technique known as lucky imaging to acquire images of the planets never thought possible just twenty years ago.

By taking high speed video (such as the one above), thousands of frames are captured.

By eliminating blurrier frames, astronomers can stack and align the sharpest frames together and compensate for the rotation of the planet to produce a final sharp image as per the one below:

Mars, as imaged above by Maggie Roque, Killarney Provincial Park Discovery leader, on the morning of September 23, 2020 with the 16” telescope housed in the Kchi Waasa Debaabing (Anishinaabemowin for “seeing very far”) Observatory. Images of Olympus Mons, Northern Polar Hood, and Valles Marineris are from NASA and ESA

Signs of intelligent life?

Back in the 1800s, the astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli thought that he was seeing “channels” through his telescope. The word “channel” in Italian is “canali,” which, if incorrectly translated, could be interpreted to mean “canals.”

The difference is important in that the former interpretation (channels) can be assumed to be natural formations whereas the latter interpretation (canals) implies intelligent life and construction techniques.

It was this latter interpretation that Percival Lowell understood, which led him to think he was seeing evidence of intelligent life.

Much science fiction literature and film has been based on belief in martians due to the early observations and interpretations. We now know that Mars is a barren landscape that contains a great deal of frozen water (in the polar caps and beneath the surface) and, perhaps in the distant past, had oceans of liquid water.

Going with the flow

One of the current hot topics in the study of Mars is the role that flowing water may have played in the development of the Mars’ geography.

Of course, if liquid water did exist in great quantities in the past, there may have been a greater opportunity for life to have formed or to even have thrived on the planet.

Indeed, many images display what appears to be the erosive outcomes of rivers, gullies and dry lake beds.

However, in a recent paper published in Nature Geoscience1, a team of American and Canadian researchers suggest that much of these features found within the Southern Highlands of Mars resemble formations found in the high Canadian north and may have been caused in a similar manner; the erosive result of glacial or subglacial activity, rather than water.

This would put a damper on the idea that Mars may have been teeming with water in its past.

Only by continuing to explore the planet with both robotic spacecraft and human explorers, will we probably finally answer this fascinating question of whether Earth is our solar systems sole home to life.

If you’re an astronomy enthusiast, don’t miss our monthly “Eyes on the skies” feature!

[1] Grau Galofre, Anna & Jellinek, Mark & Osinski, Gordon. (2020). “Valley formation on early Mars by subglacial and fluvial erosion.” Nature Geoscience. 10.1038/s41561-020-0618-x.