Our “Forever protected” series shares why each and every park belongs in Ontario Parks. In today’s post, Zone Ecologist Corina Brdar tells us Holland Landing Prairie’s story.

“The mosquitoes have been exceedingly troublesome these two days past. It is almost impossible to sleep during the night, for they are quite as plentiful and every way as michievous [SIC] as during the day.”

Sounds familiar, huh?

This isn’t a comment from a frustrated camper – it’s a 200 year old journal entry by a Scottish explorer visiting what is now known as Holland Landing Prairie Nature Reserve.

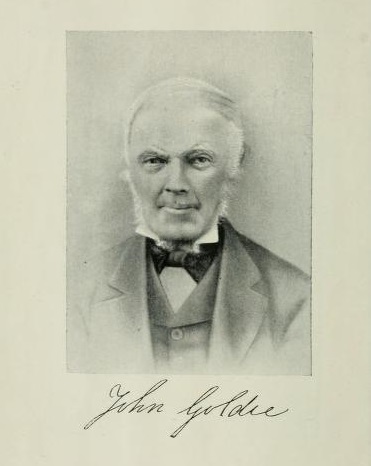

John Goldie walked (yes, walked!) from Montreal to Lake Erie in the summer of 1819.

Why would he do such a thing?

He was collecting plants, of course! At the site now called Holland Landing Prairie, John Goldie was the first European to discover and officially describe a new species of buttercup.

Two centuries later, I’m sitting at my desk on a cold, wet spring afternoon thinking about the same patch of land and the same buttercups. My colleagues and I hope the rain stops long enough for us do a prescribed burn to restore the habitat for John Goldie’s buttercup and other prairie species.

Let me tell you the story of Holland Landing Prairie from 1819 to today, and you’ll see why this tiny nature reserve is an important part of our protected areas system.

Holland Landing Prairie’s representative ecosystems

First, let’s travel back a few thousand years.

I used to think that southern Ontario was a huge swath of old-growth forest before Europeans arrived, but I was wrong. Along with towering American Chestnut trees and sky-filling flocks of Passenger Pigeons, there were zones of prairie from Windsor to Peterborough.

These prairies existed thanks to an extended period of warm, dry climate after the glaciers left Ontario and burning by First Nations. Ontario’s prairies were home to specialized plants, birds, reptiles, and insects who needed the dry, open conditions to survive – plants like the Prairie Buttercup described by Goldie.

Patches of prairie are what Goldie probably found as he trekked north up Yonge Street from York (Toronto) to Holland Landing.

Fast-forward to the middle of the 1900s

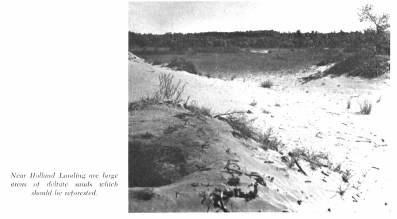

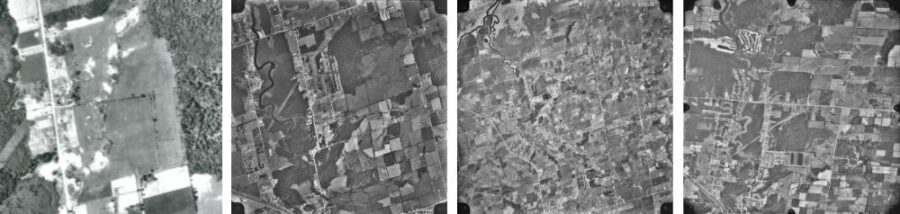

Although Holland Landing Prairie is protected as a nature reserve today, its unique ecosystems weren’t always valued. Land managers saw this sandy, open area as a wasteland in need of trees. So, sure enough, they planted lots of trees right atop the prairie.

In 1976, another famous botanist visited this area and found an open prairie community full of interesting plants, including Prairie Buttercup, amongst rows of baby pine and spruce trees.

Before Google Maps and global positioning systems, Dr. Reznicek determined that Holland Landing Prairie is where Goldie first discovered Prairie Buttercup.

In the past few decades, we’ve recognized Holland Landing Prairie for what it is: one of the last remnants of Ontario’s Tallgrass prairie ecosystems.

It was officially protected as a nature reserve class provincial park in 1994 with the goal of preserving and restoring this endangered ecosystem.

Today about 3% of the prairies Goldie and other early European explorers would have encountered are still here in Ontario.

In fact, this type of ecosystem is disappearing from all the places it was once found all over the world. That’s why we’re now working to restore the remnants that are left in many provincial parks.

At Holland Landing Prairie, that means we are slowly and systematically removing the trees that encroach on the prairie remnants. We began burning sections of the park to help the prairie recover in 2018.

Holland Landing Prairie’s representative species

I believe the only things Goldie would recognize today about Holland Landing Prairie are the mosquitoes and the remaining patches of interesting plants.

Prairie Buttercup wasn’t his only botanical find. Gardeners today love the showy orange flowers of Butterfly Milkweed (Asclepius tuberosa), but Goldie was the first European plant-lover to spot it here.

Other native species – that also happen to be garden favourites – seem to appreciate our restoration efforts.

When we monitored the plants after burning the site in 2018, we found patches of Bee Balm aka Wild Bergamot (Monarda fistulosa), Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta var. pulcherrima), and of course lots of Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardii).

These plants are indicator species, meaning when a biologist comes across them they can deduce a lot about the type of ecosystem they are exploring. In this case, these plants tell us that we’re in a prairie ecosystem with dry, warm conditions and fast-draining soil.

Goldie wasn’t an entomologist, but we think that entomologists and entomolophiles (new word used here first!) may discover specialized species that are not widely found in the province.

Stay tuned for more “Forever protected” posts about the amazing natural spaces that form our network of provincial parks.