Today’s post is from Alistair MacKenzie, our Natural Heritage Education & Resource Management Supervisor at Pinery Provincial Park.

I’ve been bird watching since the age of six. My dad was the main reason I began bird-watching, and he and I spent many hours in search of another species for our lists.

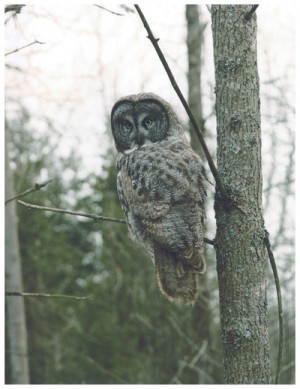

From the start, I was always fascinated by owls and to this day they are, hands-down, my favourite group of birds. You have to work hard to find owls given that they are usually solitary hunters and most do not roost together in communal groups. Many, but not all, are nocturnal and they are generally shy and reclusive.

With a little effort, however, you can be rewarded with once-in-a-lifetime experiences with owls. Across Ontario, our provincial parks offer a myriad of habitats that owls frequent – careful observers can be rewarded with stunning encounters with these nocturnal marvels.

How many owls live in Ontario?

There are two groups of owls in Ontario – typical owls or strigidae and the barn owls or tytonidae. Combining these two groups, there are eleven species of owl known to occur in the province, namely:

Tytonidae:

- Barn Owl – Tyto alba

Strigidae:

- Eastern Screech Owl – Otus asio

- Great Horned Owl – Bubo virginianus

- Snowy Owl – Nyctea scandiaca

- Northern Hawk Owl – Surnia ulula

- Barred Owl – Strix varia

- Great Gray Owl – Strix nebulosa

- Long-eared Owl – Asio otus

- Short-eared Owl – Asio flammeus

- Boreal Owl – Aegolius funereus

- Northern Saw-whet Owl – Aegolius acadicus

One other species is known from the province, but is believed to be an accidental visitor: the Burrowing Owl – Athene cunicularia.

In my years of birding, I’ve been rewarded with sightings of every Ontario species except for one…the Barn Owl, so it’s at the top of my list of species to see in the wild in Ontario.

Hopefully you can finish the list for yourself while exploring Ontario Parks!

Owls only come out at night, right?

Owls are specially adapted for life in the dark, but let me get something out of the way first: not all of the owls in the list above are active only at night.

In fact, the Snowy Owl, Great Gray Owl, Northern Hawk Owl and Short-eared Owl are often active during daylight. These four species breed in the far northern reaches of Ontario and beyond into the arctic, where summer daylight is extended and where a purely nocturnal hunting strategy could lead to empty stomachs!

In some years, these species can migrate southward well into southern Ontario and can yield great daytime observations.

270-degree vision

One of the main things that distinguish owls as a group from other birds is a highly developed sense of sight. Owls have excellent eyesight and can see well in low light conditions.

In addition, owls have eyeballs that are so large that they are fixed in their eye sockets. Fixed eyeballs prevent an owl from being able to look around while holding their head still like a human can.

To compensate for fixed eyeballs, owls have twice as many vertebrae in their necks as humans do; extra vertebrae allow the neck of an owl to rotate or twist more and allow owls to swivel their heads about 270 degrees when perched.

Pinpoint hearing

In addition to excellent eyesight, hearing is highly developed in owls. While there is variability among species, owls have evolved to direct sound into their ears in a very sophisticated way that enables them to accurately determine where a sound is coming from.

Of course, like other animals, they have an ear on each side of their head, so if you imagine a mouse scurrying around on the forest floor, they can easily determine if the prey is to their right or left as the sound will reach one ear a fraction of a second before it reaches the other.

Similarly, some species of owls have a flap of skin in front of their ear openings that somewhat shields sound. A louder sound likely originates immediately behind the owl, a muffled one in front.

The facial discs of feathers that are so characteristic of owls are believed to be sound directing adaptations that funnel sound past their eye and into the ear openings located on the side of the head.

In addition, amazingly, some owls have one ear positioned higher on the side of the head than the other one! As a result, a sound from beneath the owl hits the lower ear first, and then a fraction of a second later enters the higher ear.

If you combine all of these factors, an owl can pinpoint a sound by making a series of simple decisions – is the sound coming from in front or behind me? Is the sound coming from beneath or above me? And is the sound to my left or right? Combining all of these decisions in a split-second allows the owl to find prey in complete darkness.

Silent flight

To take advantage of these hearing adaptations, owls add another specialization to their arsenal…near silent flight.

A few simple modifications to the time-tested design of the feather enable owls to fly without making a sound! The leading edges of the primary feathers of owls have a comb-like fringe. This simple difference from diurnal raptors lessens the rippling of the edge of the feather and yields silent flight.

How do I find owls?

You need only a few tools to help you search for owls:

- good pair of binoculars

- trusty field guide

- good footwear

- backpack (complete with nutritious lunch and safety equipment)

- weather-appropriate clothes

- a companion

Scanning fields and fence posts or searching in dense conifer stands can yield owls. A favourite trick of naturalists is to search for white-wash on trees.

As owls roost during the day, they express waste from their perch which often decorates the tree with a white sheen, visible from afar.

You can also search at the base of trees for owl pellets! Pellets are compressed packets of indigestible bones, teeth and fur from the prey owls consume. Owls express pellets from their mouths once or twice a day and they can accumulate beneath frequently used roosts. A great activity is to tease apart an owl pellet (soak it in water with a few drops of dish soap) and try to reconstruct the prey’s skeleton.

Keep a camera and a log book handy when you go in search of owls and remember to submit your sightings to monitoring programs like eBird or iNaturalist.

Not sure where to start your search?

Consider speaking with park staff, especially Discovery staff, as they may be able to provide you with hints and tips as to where and when to search.

Be sure to respect owls and consider investing in a decent telephoto lens for your camera; you’ll be rewarded with better photographs and reduce your impact on the ecological integrity of our provincial parks.