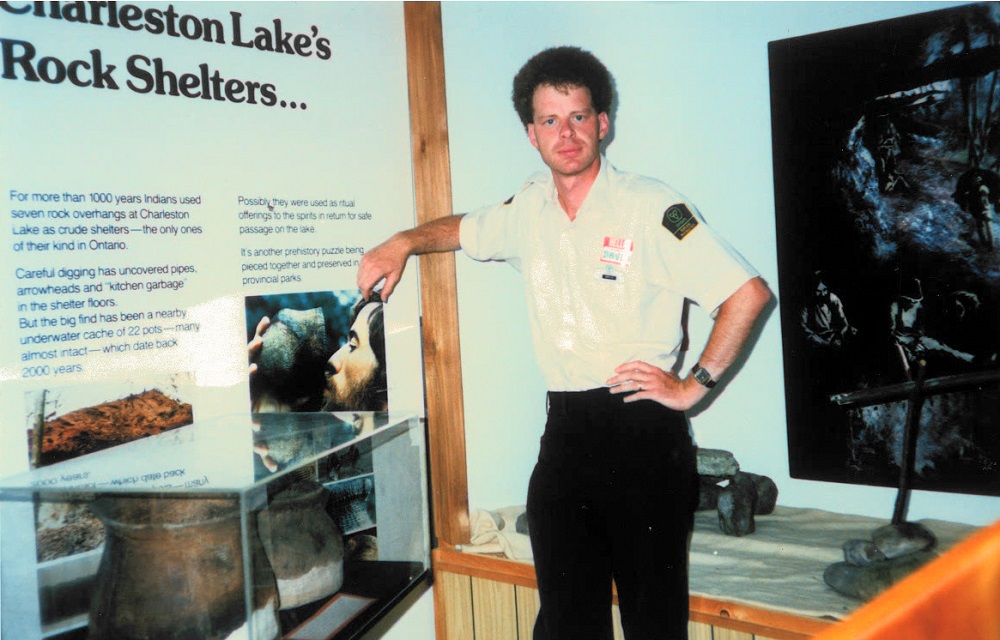

Buckle up for the ride of a lifetime! Interpreter, David Bree, is about to take us on a journey down memory lane.

After 32 years, the end is near.

Hi, my name is David Bree and I have worked at Ontario Parks as an interpreter (also known as a park naturalist) for over half my life.

As I go through my final year as an Ontario Parks employee, I have embarked on a retirement nostalgia tour of the parks I worked at.

Join me as I reconnect with some of the great natural landscapes in Ontario, discovering what has changed and what remains the same in these parks.

Jumping in head first

First up, appropriately enough, is my first park Charleston Lake Provincial Park.

I was late coming to a job in parks, having spent most of my 20s as an academic and exploration geologist. In 1988, I was in my fourth year of a two year master’s project. Nothing was going well, experiments were not working, and my scholarship had run out, so I was procrastinating by finding joy and solace in my personal exploration of the natural world.

I say personal, but my exploration was shared with my wife, who was already working as a naturalist at Sandbanks Provincial Park. One day in late June 1988, she came home and said the naturalist at Charleston Lake had just taken another job and they were looking for a replacement — now!

Hey! A chance to put my master’s even further out of mind, keep learning about nature, and make some money.

I borrowed a friend’s car and went down for an interview and was hired the next day. I was in the right place at the right time. Little did I know that lucky break would be the start of a lifelong career.

Revisting

On June 11, 2020, I drove the two hours to Charleston Lake.

I’ve been back a couple of times since, but today seemed different. I was a little nervous, a little excited, and it was easy to drift back 32 years. Though I had been to Charleston Lake a few times as a visitor before I started working there, I learned that working in a park gives you a different perspective.

It becomes yours. You look after it, you learn its secrets and moods, and it becomes very personal.

Your first park, like your first love, always remains special.

I arrived early and immediately headed for my favourite trail – Quiddity.

Hitting the trails

Quiddity is a short trail, but it’s marvellous for showcasing the natural diversity of the park: forest, two boardwalks over shrubby swamps, and a rocky lookout, all in less than 2 km.

The trail head is just steps from the Nature Centre, where I worked 30 years ago, so it was easy to do a walk on the Quiddity. For four years, I did at least one survey a week, recording all the flowers blooming along that trail. Over 50 species were listed.

Today I noted about a dozen, including Tufted Loosestrife in the swamp and Maple-leaved Viburnum in the forest. It would be interesting to see if flowering dates have shifted in three decades. Perhaps a retirement project.

Fly, dragonfly!

It was along here that I developed my lifetime fascination with dragonflies.

There were so many, and all different colours: yellow, red, green, blue, some with patterns, some plain. But what were they?

As a park naturalist I should know, I wanted to know. But there was no iNaturalist to post pictures on. In fact, there was no internet or even digital photos.

Taking a picture to show someone would require a wait of a week or longer as film was sent off to be developed. You wouldn’t even know if your picture was in focus until then!

No field guides for dragonflies and the technical guide was out of print. Even the Queen’s University library didn’t have it. I was stuck. Indeed, I had to wait for over five years before the technical guide was reprinted and I could start identifying dragonflies.

By then, I had left Charleston Lake, but the images of darting dragons and the joy they brought have stayed with me to this day.

My recent visit did not disappoint me. There still be dragons on the Quiddity.

My study of dragonflies has dropped off the last few years as my eye sight has started to fade and my catching reflexes slowed, but the Quiddity had me shooting pictures left and right in renewed excitement (digital photography is so great!).

I easily identified over a dozen species in an hour, including two species rare in Ontario: Harlequin Darner and Lilypad Clubtail. The latter was a pair in a wheel, a mating configuration unique to dragonflies and damselflies.

Rediscovering Discovery

The rocky lookout at the end of the trail was as pretty as I remembered. It was here that I felt granite under my boots once again. Most of my geology career and the first five parks I worked at were on the Canadian Shield.

There’s something about feeling the hard, ancient root of the continent under your feet that connects you with “wild” Canada. I’ve missed that at Presqu’ile.

The Discovery Centre wasn’t open so I couldn’t check out my old office, but I did see the campfire circle behind. It was essentially the same, a small and intimate space.

It was here that my supervisor, Mike, and I proved time again that you could present fun, educational sing-along programs with two guys that did not play musical instruments and sang like crows.

We did a lot of skits.

For songs, I learned to follow the enthusiastic clapping of the Girl Guide-types in the front row in order to keep the rhythm and beat, which I would inevitably lose on my own.

I learned the action song “Swimming, Swimming in Charleston Lake” which I carried with me from park to park for the next two decades, changing the name of the lake as appropriate where ever I was.

Good memories, but a guitar player would’ve been nice.

A geologist’s dream

I walked through the screen of trees into Bayside Campground that 30 years ago was essentially a field.

Now it was well-wooded and the sites were screened and private. Many of those trees had been planted in the years just before I started working.

As a geologist, the Sandstone Island Trail has always beckoned. Geology and landscapes unique in Ontario are showcased along its first 1.5 km. Here, 500-million-year-old conglomerate and sandstone rock lies directly on billion-year-old granite.

The actual contact can be seen at one spot. This nonconformity is rarely seen and gets geologists quite excited (really, ask one!). More visually appealing are the rock shelters. The sandstone and conglomerate have eroded at different rates, forming overhangs.

These rock formations have yielded artifacts that indicate they sheltered ancient First Nations hunting bands and early French voyageurs. The rock shelters look the same as when I led hikes through them.

Geology doesn’t change much, at least in the span of a human life. But everything changes and these shelters will one day collapse, a fact I always liked to point out during my guided walks to get people moving again.

Forest finds

Not all the changes I noted were good. I was distressed not to hear a single Cerulean Warbler along the road where I could hear seven singing males in the past. The current park naturalist, Chris, had told me this species at risk had disappeared some years previously, but I didn’t want to believe it.

Despite the forest looking healthy here, their absence indicates that no park is an island and many of our birds require habit and protection throughout the Americas.

While most of the forest looked good, I did notice quite a bit of the invasive Garlic Mustard in a few spots. Though she probably knows, I resolved to mention the spots to the zone ecologist and the superintendent.

Back in 1988, there were no zone ecologists and looking after the park’s ecological wellness. This fell to individual park staff. Depending on interest, knowledge, and experience, that kind of work could be overlooked.

We basically let ecology look after itself and just worried about customer service. Now we control invasive species, do restoration work, reroute trails away from sensitive areas, and more.

Up close and personal

I had to drop by the amphitheatre, the site of my first formal park presentation.

It still looks the same. One of the prettiest amphitheatre locations in Ontario Parks, it’s accessed along a rocky ridge and surrounded by beautiful hardwood forest.

Such a natural setting can have its drawbacks, though. I clearly remember the evening that my talk was interrupted by a fat Grey Tree Frog falling out of the tree above and landing with a loud splat on the stage in front of me. Luckily it was okay, and after a quick discussion on tree frogs, was placed back into the forest and I went on with my presentation.

There was no continuing on the night two Barred Owls had a long and very loud conversation right overhead. Calling back and forth across the audience, I could only sit down with the visitors and change the talk into a discussion of owls (and how rude they could be at times).

No park naturalist can compete with the real thing. Why would they want to?

It turned out to be a far better program than one I could do. I don’t remember what the topic of my talk was that night, or if I ever went back to it, but I sure remember those owls and I am sure the audience does too.

Turning back time

Before leaving Charleston Lake, I made a point of dropping by the office to say “hi.”

Amanda, the park clerk, was there. Park clerks are the backbone of the administration of a park. While the public doesn’t see them much, they keep the park budgets and are the go-to person for information about spending or pay and benefits.

As I always tell my staff – be nice to the clerks, they are the ones that make sure you get paid!

Amanda was there 32 years ago when I first stepped into the office. She looks much the same as the day she had me sign my first park contract. Back then, she was also taking camping reservations, which were written down on big poster boards.

A cancellation required her to break out an eraser to open the spot again. A crude system, but it worked quite well. Today she seemed a little bemused by my nostalgic re-telling of her place in my life history. She has probably set up hundreds if not thousands of contracts in her career, but the one she did for me was a turning point in my life.

I found that despite being thrown into my first summer season with no experience and little prep time, I had a knack for story telling.

That combined with a love of nature, history, and an eagerness to learn positioned me perfectly as park naturalist material.

Who knew?!

I began my transition from geologist to naturalist and spent four glorious seasons at Charleston Lake before moving on to my next park: Bon Echo Provincial Park.