Today’s post was written by Jill Legault, Quetico Provincial Park‘s history buff and information specialist.

The ability to fly to otherwise inaccessible locations in Quetico Provincial Park revolutionized park operations in the 1930s.

Suddenly, winter supplies could be flown in to ranger cabins, poacher’s tracks could be seen from the air, forest fire management drastically improved, and American tourism increased.

The ambush of Dusty Rhodes

Poaching was the main concern soon after Quetico’s inception in 1909. By the 1930s, poachers had the ability to fly out their furs with bush planes, but planes also meant that poachers’ tracks could be seen from the air.

Some poachers even strapped moose hooves on their feet to try and disguise their movements from park rangers!

Here is an excerpt about ambushing a poacher from Quetico Park’s Fascinating Facts, published by the Friends of Quetico:

“In 1931, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police set up a stakeout at Lac La Croix for a notorious fur poacher and bush pilot by the name of ‘Dusty’ Rhodes. When Rhodes landed, the Mountie posing as a tourist suddenly canoed to the plane followed by an Ontario Provincial Police Constable. Rhodes attempted to take off with the Canadian officer hanging onto his floats. Drawing his service revolver, the Mountie smashed the cockpit window and placed the muzzle of the weapon against the pilot’s head, commanding ‘Put ‘er down!’ Rhodes did.”

Improving rangers’ lives

In 1934, George Delahey was appointed District Forester in Fort Frances. He was also a pilot, and his use of aircraft changed the lives of the Quetico rangers. Planes such as Gypsy Moths, Beavers, and the larger Hamiltons were all used by the park to bring in supplies. Many cabins and fire towers were built or upgraded with the new ability to fly in construction materials and skilled workers.

“Being a world war pilot, George Delahey flew the plane and got around and saw how awful some of our cabins were. He had Bob Halliday, Albert Lemay and I build a nice log cabin on Cache Bay in 1938.”

— Art Madsen

The first all-metal aircraft of the Provincial Air Service, the Hamilton H-47, was used to bring Bob, Albert, and Art the supplies needed to build the new cabin.

The business of tourism takes flight

After World War II, aircraft were abundant and Quetico saw a staggering increase in American tourists. Planes became more accessible to the public, and soon tourists began flying up from all over the United States.

By 1948, it was reported that Ely, Minnesota (a southern access point to Quetico), was the largest float plane base in North America!!

Forest fire management

Fire suppression changed drastically after 1936, when fires consumed more than 76,800 ha of Quetico’s forest, marking one of the worst fire seasons ever recorded in the park. Since then, Quetico has seen a myriad of planes and helicopters as technology advanced across all of Canada.

One of the first aircraft used by the park for fire suppression was this Big Hamilton seen above on Saganagons Lake.

The Canso water bomber (above, left) was retired in 1988 to make way for the CL-215 (above, right), which was known to be the most effective water bomber at the time.

The Beaver’s legacy

In 1947, the Ontario Provincial Air Service ordered 12 Beavers for northwest ranger duties. The Beaver soon became one of the best-known bush planes in the north, and is still used in Quetico today.

In modern times, the primary purpose of the Beaver is to do a weekly park supply run. Every Wednesday, during Quetico’s operating season, rangers fly to the four remote entry stations and deliver supplies. To maximize efficiency, members of portage crew are often dropped off or picked up at the same time.

Saving the day

Some of our Assist Emergency Services operations also continue to use Beavers.

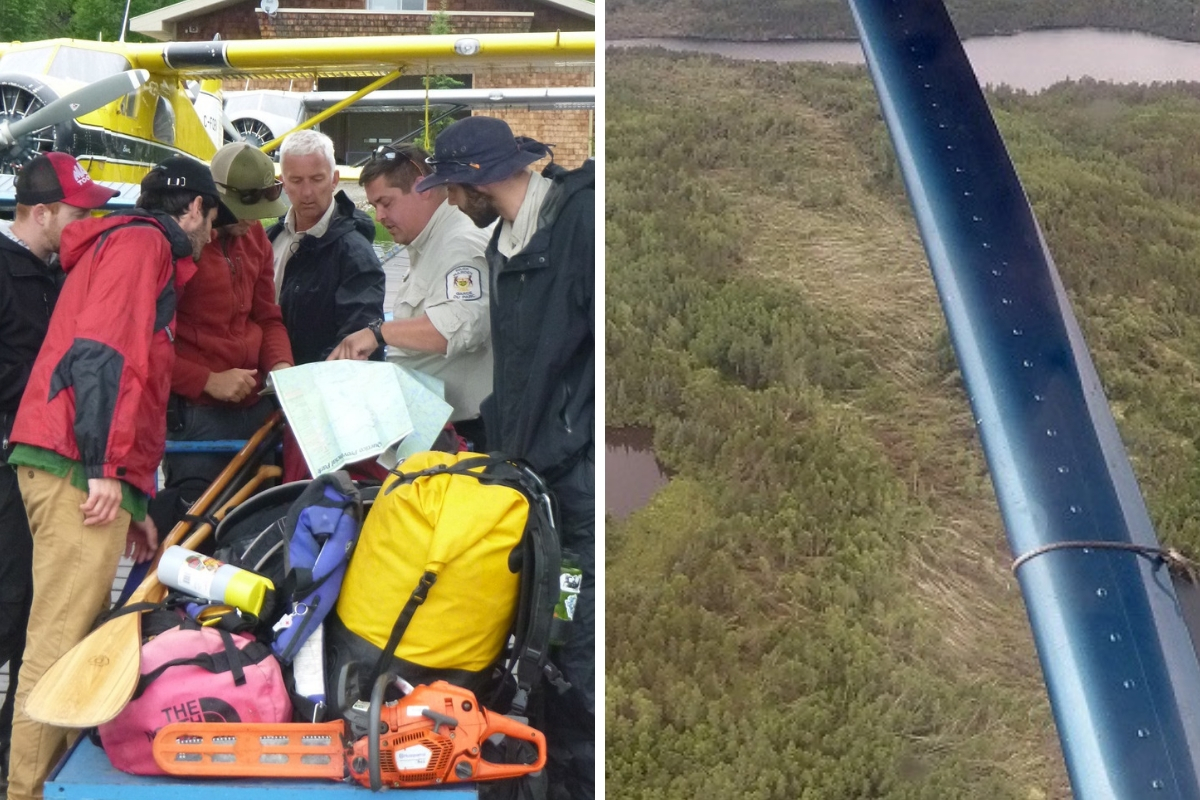

In the above photo, Quetico Park staff meet with pilots from Sapawe Air Ltd. to discuss the damage caused by the tornado that occurred on July 6, 2017.

Park staff flew to the area the next day to find several trees flattened along a 100 m wide and nearly 2 km long stretch of the park. Chris Stromberg and Eric Boyd, of the portage crew, were sent to clean up portages.