Today’s article comes from our bird recording specialists, Zone Ecologist Ed Morris and Zone Operations Technician Rebecca Rogge.

Birds are interesting. Most are visually striking, with noteworthy songs to match their brilliant feathers.

They are also very important.

Birds contribute to the health of our environment. They disperse seeds, pollinate plants, and help to control insect populations.

They have direct and indirect effects on human health and well-being as well.

The medical community recognizes the health benefits of spending time with nature and for many people, their connection with the natural world is through birds.

Monitoring birds across a huge protected area network: Why, what, and how?

Birds are excellent sentinels for environmental changes.

They are relatively easy to observe and document. If we observe declines in one or more species it leads us to ask “why?”

Is it a reflection of the general health of our environment? Of their wintering area? Of their migration route? If so, how can we improve the situation?

Your park visit funds bird monitoring and protection

Did you know 100% of proceeds from reservations and purchases are reinvested in parks?

Thanks to an increase in visitation in recent years, Ontario Parks has had the opportunity to support more projects and research, including key monitoring and restoration projects for bird communities in parks and conservation reserves.

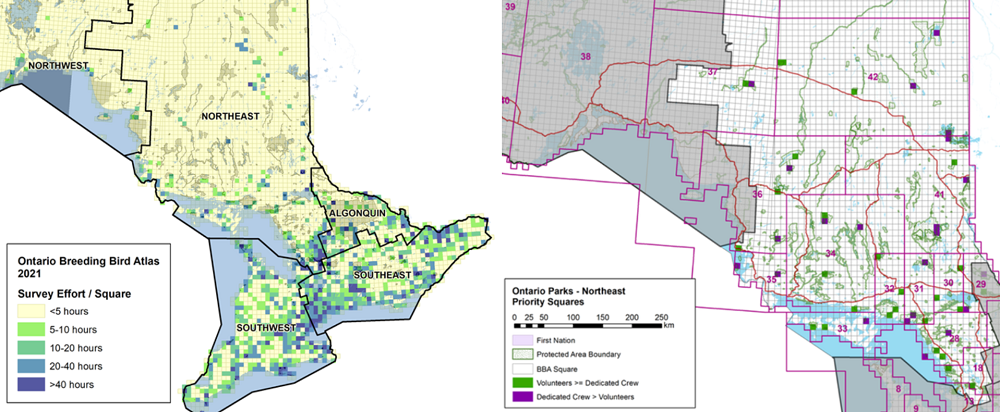

Ontario Parks is currently participating in its third Breeding Bird Atlas initiative from 2021-2025.

The goals of the Atlas are ambitious: to survey breeding birds across all regions of the province and assess the population status and breeding success of approximately 300 species.

It makes perfect sense for Ontario Parks to coordinate with, support, and contribute to this well-organized, province-wide initiative!

Volunteers conduct much of the Atlas surveys. In fact, it may well be the largest community science project in Canada!

However, while most of Ontario’s population is southern, the protected areas in northern Ontario cover millions of hectares.

The north is also such a food-rich environment that it is the destination for migratory birds. So how will we ensure the north is surveyed adequately?

Setting priorities

It won’t be possible to survey in every square kilometre in northern protected areas.

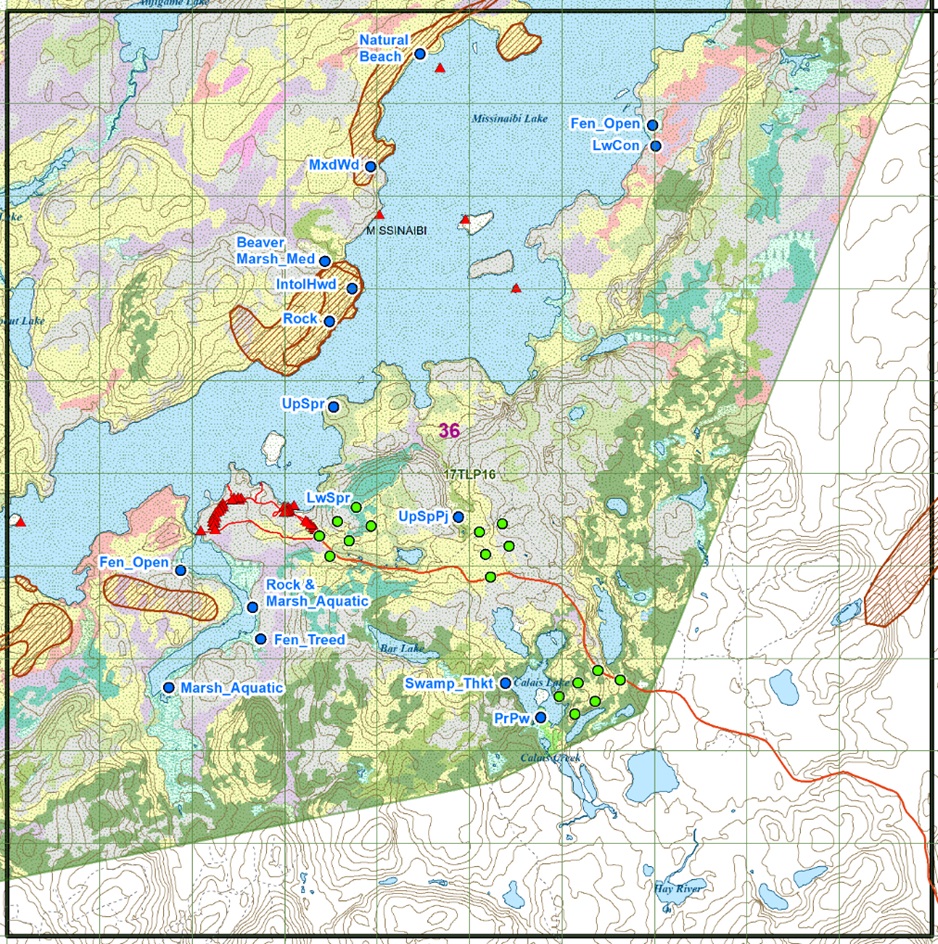

Within each region, we selected specific 10×10 km squares that overlap with protected areas, also contain roadless areas, and yet are accessible to surveyors traveling on water, on hiking trails, or on portages.

Finding experienced birders

To ensure we get good information on breeding birds, Ontario Parks encourages keen, experienced birders to survey in provincial parks and conservation reserves.

Experienced birders can enquire about rate reductions at under-surveyed parks in exchange for atlassing.*

These tend to be the northern, more remote parks.

In some remote and under-surveyed places, Ontario Parks or Atlas volunteers organize special events known as “Square Bashes.”

They are open to anyone with an interest in birding and the Atlas, including beginner birders.

Please contact the Atlas for more information!

* Not all requests can be accommodated, and requests take time to review. Plan ahead! Please contact your Atlas regional coordinator for further information.

Dedicated staff and resources

In 2022, Ontario Parks hired two resource technicians to conduct bird surveys in northern protected areas, particularly focusing on off-road surveys.

After the end of the breeding bird season, these staff switch over to other forms of ecological monitoring and resource management activities, such as invasive species management.

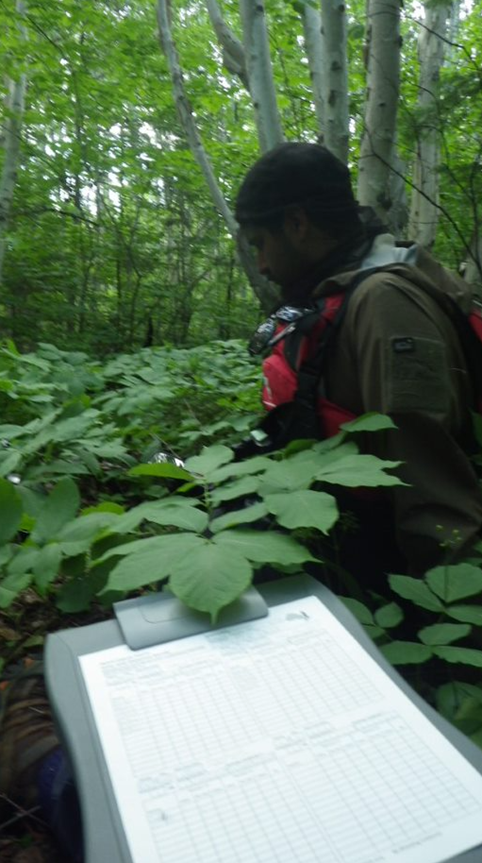

So what does a day in the life of a bird-monitoring technician like?

Resource Steward Rebecca Rogge gives us a taste.

This year, I worked out of Wakami Lake Provincial Park and Missinaibi Provincial Park.

Most days between May and mid-July began with waking up at 5:00 a.m. to prepare for the day. The rest of the park staff were happy that coffee was already brewed when they got up!

We were usually out the door between 6:00 and 7:00 a.m. “Bird O-Clock” was the peak singing period between dawn and 10:00 a.m.

Our morning consisted of traveling to pre-determined survey locations. Once there, all the birds we saw or heard in a five-minute period were recorded before moving on to the next site.

While listening and making notes, we also made stereo recordings using a handheld recorder. If we missed something, or were unsure of a particular species, we could refer to the recording if needed.

Off the beaten path

We travelled to many places not visited by the public. Getting there required advanced preparation and an intrepid spirit.

Safety always came first.

Sometimes we had to wait until the fog lifted, until it was bright enough to see in dense forest, or to be able to see shoals if we were travelling on water.

Wind, temperature, heavy rain, thunder, and lightning also affected our schedule.

Some forests were extremely dense, while storm damage (e.g. blowdowns) in others created obstacle courses of fallen logs. Navigating in these areas required a high-level of old-school map and compass skills. It was slow-going and easy to get turned around.

However, birds thrive in many types of environments.

If we only visited the easy-to-access locations, we wouldn’t be documenting the full range of species present in parks or conservation reserves!

In Missinaibi Lake, for example, Mourning Warblers and Canada Warblers seemed to love the disturbance created by a tornado that swept through part of the park in 2015.

Surveys in marshes, fens, bogs, and swamps required us to wear rain boots or chest waders.

We had to test our footing each step of the way to avoid becoming one of those bog mummies that archaeologists get so excited about!

The mosquitos and blackflies need to be experienced to be believed, but preferably from the inside of a bug jacket. Really, there was no escape.

Being two places at once

After the morning point counts were completed, we travelled to additional sites to set up automated recording units (ARUs).

These were programmed to make five-minute recordings many times a day, beginning a few hours before dawn to a few hours after. They began recording again shortly before dusk until a few hours after.

These devices effectively allow us to listen in more than one place at a time during the breeding season.

However, they are also beneficial for capturing information about nocturnal birds like Whip-Poor-Wills, Common Nighthawks, owls, as well as hard-to-find marsh birds.

They can also collect information on northern amphibians as many frogs and toads are also singing in the wetlands. We’ve even recorded howling wolves!

Early morning shifts means being done by mid-afternoon and sometimes enjoying a siesta or exploring these amazing spots.

It also allowed me to visit the local grocery store, which closes a bit too early for most park staff.

In my off-time, I continued to revisit bird hot spots with my camera to improve records of waterfowl and birds on nests.

Wondering how you can contribute?

Visitors and community scientists are the backbone of the Breeding Bird Atlas. We encourage all who are interested to visit our northern parks and submit their birding observations.

Can’t make it out to observe but still looking to support the Atlas? 100% of proceeds from reservations and purchases are reinvested in parks. This reinvestment includes funding this important work.

Whether you’re an experienced or new birder, you too can contribute to the Breeding Bird Atlas! Ready to join the ranks? Learn more about the Breeding Bird Atlas to get started.

Special thanks to Rebecca Rogge for providing photos for this article.