Today’s post comes from our Discovery Specialist (and history buff), Dave Sproule. Header image source: Minnesota Historical Society.

Over 200 years ago, George Bonga paddled fur trade routes throughout the Great Lakes region.

He also acted as a canoe guide, a translator, and eventually a trader with his own trading posts.

In honour of Black History Month, let’s take a look at the life of George Bonga.

A fur trading family

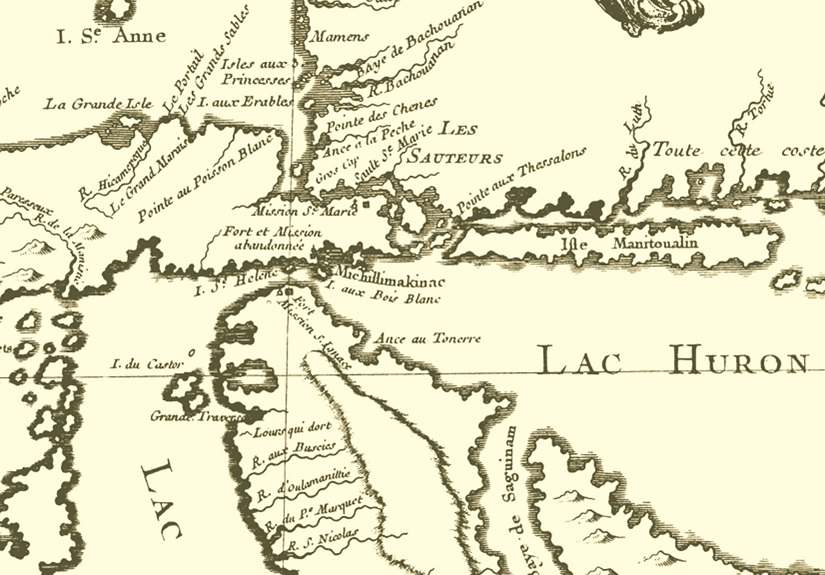

George’s grandparents, Jean Bonga and Marie Jeanne, were servants to a British Army officer based at Fort Michilimackinac in the 1780s, located where Lake Michigan and Lake Huron meet in present-day Michigan State.

The fort was an important trade depot developed by French fur traders, coordinating canoe brigades going to posts throughout the western Great Lakes and beyond.

It only became a British fur trade depot after 1760 when Canada became a British colony.

When Jean and his wife were released from their contract, he joined the fur trade at Fort Michilimackinac.

Their son Pierre, George Bonga’s father, was raised in the fur trade, and became a voyageur and guide. Pierre worked for the North West Company and often travelled to Red River Country, now part of southern Manitoba. He was known to have travelled with Alexander Henry the Younger and other fur traders.

Henry was a partner in the North West Company, a trading enterprise comprised of several independent fur traders based in Montréal. The NWCo was a major rival of the older Hudson’s Bay Company, and the two companies competed fiercely for control of the trade across the northern part of the continent.

Pierre moved to the western end of Lake Superior where new trading depots had been established, like the inland headquarters of the North West Company at Grand Portage.

Pierre worked in the trade in the Minnesota territory on the western edge of Superior, and married a woman named Ogibwayquay from the Ojibwe Nation.

Birth of an adventurer

George was born in the territory in 1802, before the boundary between the U.S. and Canada had been surveyed.

As a young boy, his parents sent him to school in Montréal. This was his first trip through the Great Lakes and up the French River.

When he returned to his parents, he spoke English, French, and Ojibwe, and had a solid education.

His education and knowledge of languages would serve George well throughout his life as a voyageur, translator, and fur trader.

As a teenager, George was part of an expedition to find the source of the Mississippi River, hired for his canoe-handling skills and knowledge of the Ojibwe language. Thanks to his language skills, he was also involved in treaty negotiations with the Ojibwe.

His bush skills also included tracking, which helped him catch a suspected murderer in 1837.

George joined the American Fur Company, founded by American businessman John Jacob Astor, a rival to both the Hudson’s Bay Company and NWCo.

A changing trade

By 1842 the fur trade had changed significantly.

The American Fur Company went bankrupt, and the Hudson’s Bay Company absorbed the NWCo in a merger forced by cutthroat competition and growing debt.

By the 1850s, the fur trade was in decline, and beaver felt hats were replaced by silk ones.

George adapted to these changes.

He built his own trading posts in the remote forests of northern Minnesota, trading with his mother’s people, the Ojibwe Nation.

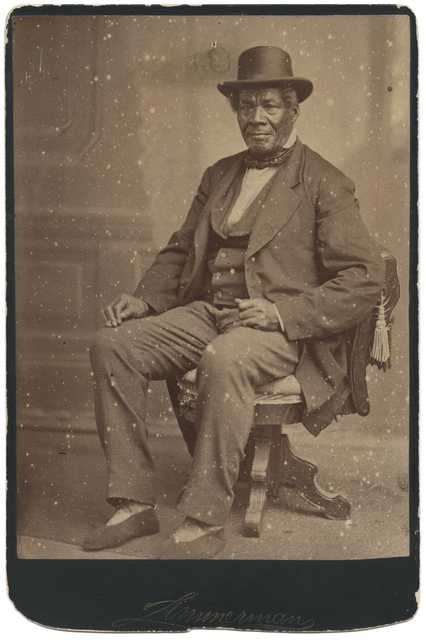

By the time of this 1870-era portrait, he had become a successful dry goods merchant, a respected businessman, and a figure in the region.

A day in the life

George was one of many voyageurs (from the French for traveller) who were the backbone of the Canadian fur trade from the 1680s until the 1850s.

Young French-Canadian farm boys from the St. Lawrence River valley would sign up with independent fur traders based in Montréal to paddle thousands of kilometres upriver and across the Great Lakes.

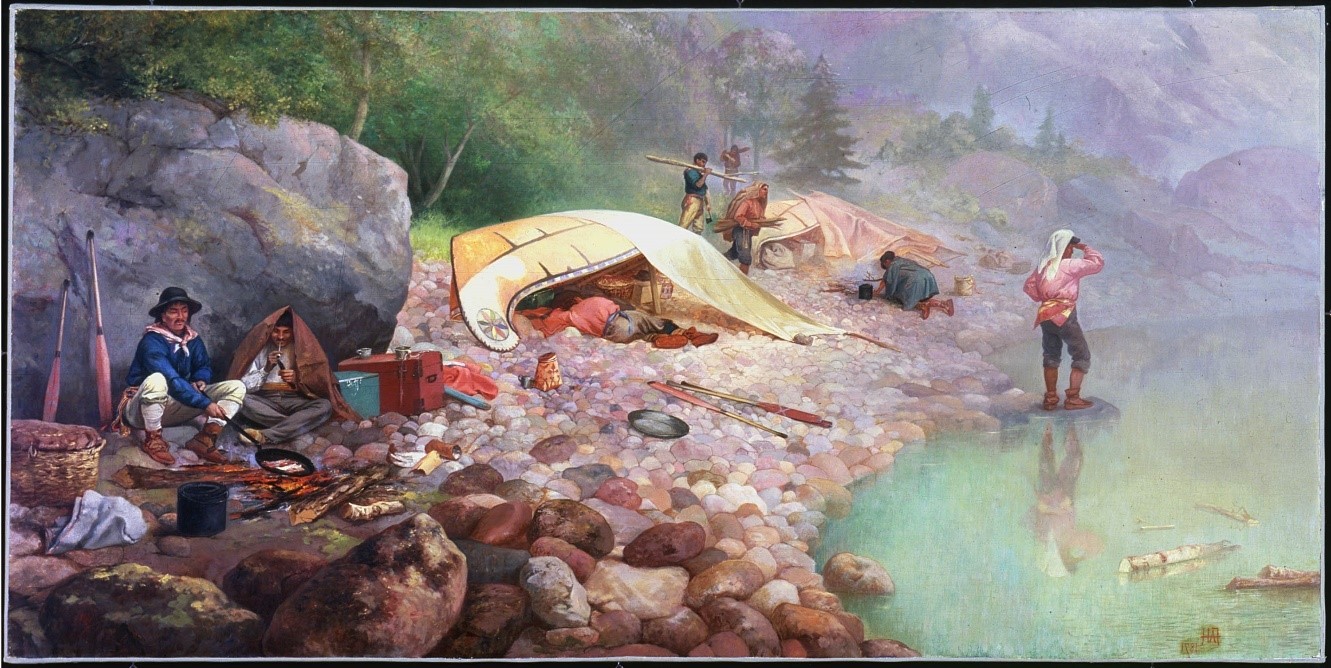

They travelled in large canoes filled to the brim with goods destined for distant trading posts scattered across the north country.

A team of voyageurs, from six to ten depending on the size of the canoe, paddled the canoe and carried it, and all of the cargo, across portages that linked lakes to form “canoe routes.”

Long before roads, the portages and waterways of the north were the highways of those days.

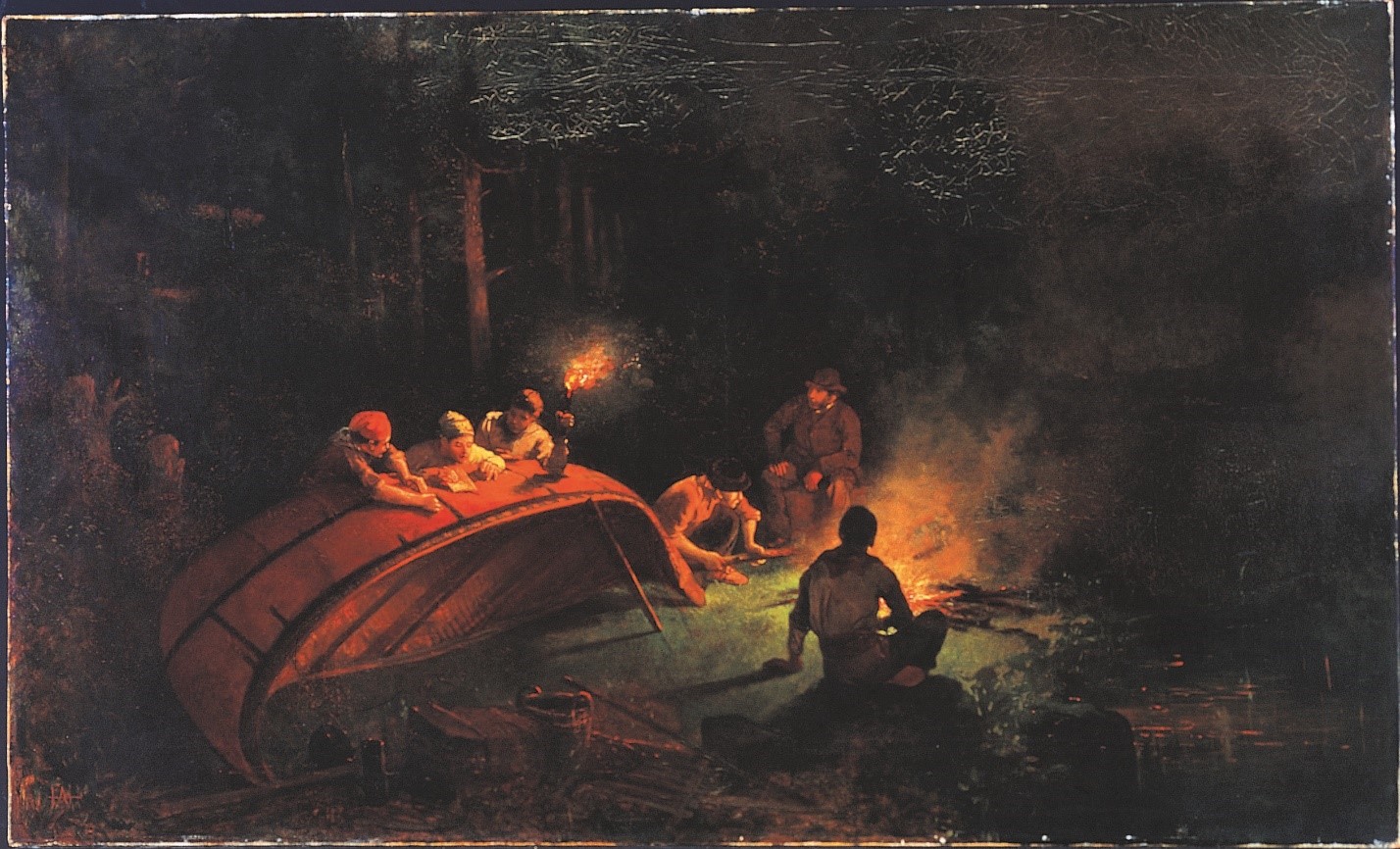

Voyageurs would start their day in the dark, before breakfast, rolling out of their “beds” beneath overturned canoes.

Paddling fifty strokes a minute and keeping time with songs like “Alouette” and “Roulant ma Boule”, the men were in their canoes for as much as 16 hours a day. George was said to be a very good singer.

Every hour there was a “peep” break, and they would take out their clay pipes and fill them from the tobacco pouches hung around their necks.

The voyageur’s most important tool: the canoe

Over thousands of years Indigenous nations developed a continental trade network across North America.

The area that is now Canada and parts of the northern U.S. is laced with a web of lakes and rivers that Indigenous traders travelled by canoe.

The canoe is easy to build from materials found in the forest, light enough to carry over trails between lakes, and easy to repair when damaged.

Fur traders also used the Indigenous canoe, made from waterproof birchbark wrapped over cedar ribs, stitched with strong spruce roots, and sealed with spruce gum mixed with campfire ash and animal fat.

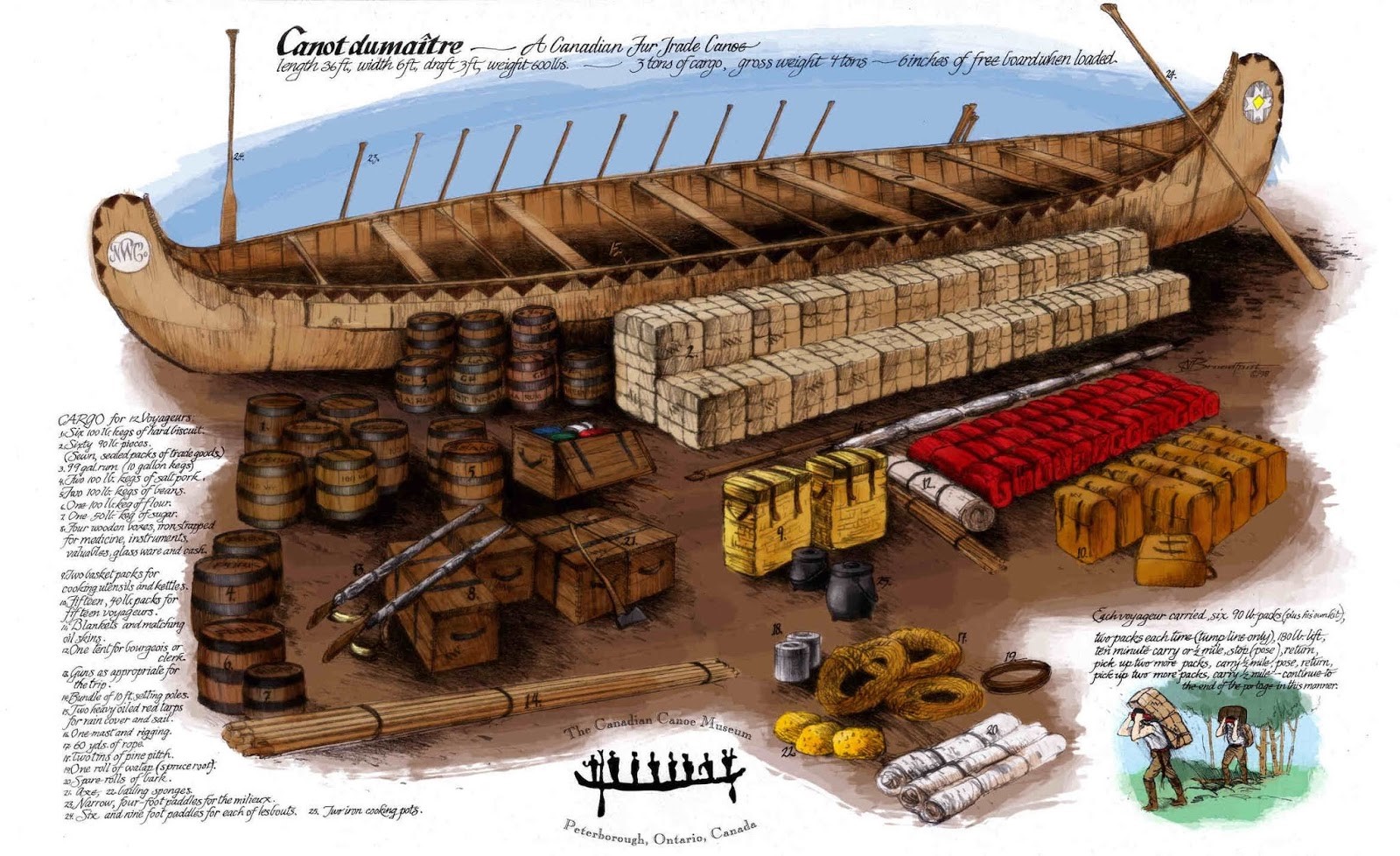

The canoe grew larger and larger in the early years of the French fur trade, and by the early 1700s had become the 10 metre, 280 kilogram giants known as the canot de maître (master canoe), or Montréal canoe, plying the main trade route between Montréal and the west end of Lake Superior.

Canot du nord were smaller at 8 metres long, and designed for the smaller waterways and portages beyond Lake Superior. These canoes could be carried by two men, instead of the four needed for the Montréal.

The canoes grew to carry more trade goods, each with three and a half tons of packs, wooden boxes, and barrels containing copper kettles, iron axe heads, blankets, muskets, many other items, and of course voyageurs.

The canoe was filled with so much cargo that voyageurs who were short, wiry, and strong were chosen as they took up less room.

George Bonga was an exception. Instead of short and wiry, he was very tall. At 6’6” he was at least a foot taller than the others. He must have been careful not to go through the bottom of the canoe!

George was said to be very strong, and stories of him carrying four 90 lb packs, called pièces in French, made him a legendary figure in the fur trade, where tall tales were a fireside pastime when voyageurs made camp.

Paddling the French River

The French River was a key link in the main fur trade route to the west.

There were other waterways and routes to the north, and through the Great Lakes to the south.

However, even with dangerous rapids and difficult portages, the French remained the key trade route between Montréal and the Indigenous nations of the Great Lakes and beyond.

When a brigade of canoes reached the French River, they could often paddle its 105 kilometre length in just a day and a half downstream, shooting dangerous rapids and risking the capsizing of the canoe and all its contents.

As most voyageurs could not swim, this was very risky indeed.

Celebrating Black History Month

In honour of Black History Month, we remember George Bonga as a voyageur and woodsman.

Today, visitors can find out more about Indigenous cultural heritage and trade routes, the Canadian fur trade, and more, at the French River Provincial Park Visitor Centre.