Today’s post comes to us from David Bree, former Discovery Program Lead at Presqu’ile Provincial Park.

Butterball was a bit of a miracle child.

The way the year went, it was amazing that his egg was ever laid, let alone hatched. And he never should have flown.

But, somehow, he did.

To truly understand Butterball’s story, and the miracle it was, we must go back eight years. And oh yeah, you should know: Butterball is a Common Tern.

The struggle of the not-so-common Common Tern

Despite their name, Common Terns are not that common, and they have been declining in the Great Lakes’ basin for years.

This is what attracted water bird scientists Dr. Jennifer Arnold and her partner Dr. Steve Oswald from Penn State University to Presqu’ile back in 2008.

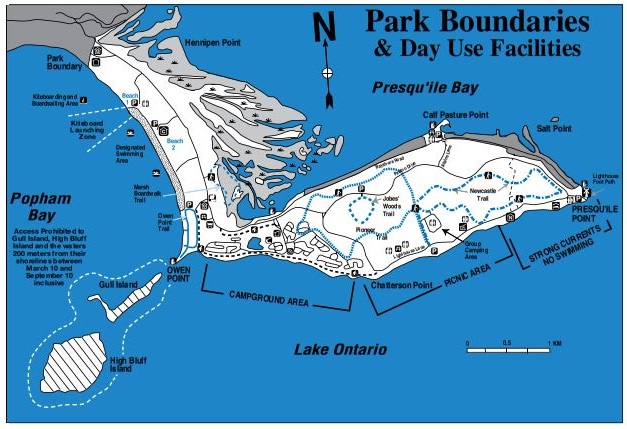

Presqu’ile had Common Terns nesting among the other water birds out on Gull Island. What made the park’s terns so unique is that they were the only sizable colony in the Great Lakes still using a natural habitat to nest.

The other terns were all using human-made structures, like navigation platforms and breakwaters.

Like other colonies, our terns were declining

Part of that was because they are the smallest of the 35,000 bird pairs trying to nest on Gull Island and they find it hard to find space.

But that doesn’t explain everything.

Through their research, supported in part by Ontario Parks and the Friends of Presqu’ile, Arnold and Oswald found that the terns tended to have two nesting periods.

The late nests had almost no chicks survive, and the first nests had lower than expected success. It was found that Black-Crowned Night-Herons, nesting on nearby High Bluff Island, were eating all the chicks!

What to do

Presqu’ile’s Management Plan allows for wildlife habitat enhancement based on science, and it was decided that the Common Terns needed help.

In 2014, researchers and park staff built an enclosure for the terns to nest in. This was a grid of wires, about 65 cm off the ground, that allowed the small Common Terns to land, but kept out bigger birds (which, on Gull Island, was everything else!).

The tern enclosure was a success. Many more chicks were surviving to fledge (fly away).

Over the years, the enclosure was modified and made bigger, until, in fall of 2018, one of the biggest enclosures yet was built in anticipation of the 2019 breeding season.

But then came the waves…

Things started well in 2019. The terns came back in May and started setting up their colony in the protected grid.

But as spring rolled along, Lake Ontario’s water level got higher than usual.

Much higher. Record high.

The lake was lapping at the structure and when a wind storm hit in late May, the nests were washed away.

Common Terns are nothing if not persistent and they nested again. But on June 4, a storm washed away all the nests and the grid system itself was destroyed.

The terns tried again on the other side of Gull Island and again the colony was washed away on June 12.

Surely this would be it; they would not try again.

A final attempt

But the urge to reproduce is strong and the terns tried once more, this time on High Bluff Island.

High Bluff Island is higher and drier, but Common Terns have never nested there.

In many years, they wouldn’t have a chance on this island. Foxes and coyotes are known to live on the island, and no ground colony of birds can survive such pressure.

However, in 2019, there were no such predators on High Bluff Island.

Finally, a lucky break!

But was it too late?

The colony started almost a month late.

Latest of all was Butterball.

Not yet a chick, Butterball’s egg was the first egg laid in Nest 63, one of the last nests of the High Bluff colony.

Butterball was the only chick to hatch from that nest, and the last in the colony to do so on July 20.

He was given a band on his leg: #599. It was a miracle he had managed to get this far, but would he ever fly?

The last chicks hatched in a year often never learn to fly in time, let alone learn to hunt on their own. In fact, most young birds don’t survive their first year; there’s simply too much to learn, and and our chicks were starting from behind.

And what about those chick-eating night-herons?

They were nesting right there beside them!

But our team of researchers and park staff were ready for that threat. Once the colony was established on High Bluff, we sprang into action, building a grid around the new colony. The tern chicks would be safe (from night-herons anyway).

A race against time

In order to grow fast and learn to fly in time, the chicks would need lots of food. Again, luck came into play.

The high water earlier in the spring had produced a pond on High Bluff Island that the carp had spawned in. That pond was now cut off from the lake and was full of baby carp. A ready supply of small fish for hungry young, right beside the colony!

The chicks grew quickly, and our last chick one of the fastest. Number 599 was 35 g on July 23, 85 g six days later, and a very plump 135 grams by August 6. This last weight is about 20-25 g fatter than an adult tern.

It is not unusual at high-quality inland sites like Presqu’ile for a chick to be bigger than an adult for a while. They usually lose that extra weight in a week or so. They must, as they are likely too fat to fly!

This is when Butterball (a.k.a. #599) was christened.

Over the next 7-10 days, all the other birds flew off and there was one round chick left, all by himself in the grid colony.

Well, not quite all by himself.

His parents remained, defending the nest and feeding him as late as August 16. Such dedicated parents, but would he ever fly? “Such a large bird, stop feeding him,” we thought.

August 19 was the last staff visit. The adult terns were still there, but good news: Butterball was down to 120 g.

That should be good enough to fly, but could he? Would he?

Did Butterball make it?

Normally, this would be the end of the story, with us never really knowing Butterball’s fate.

It is very difficult to find an individual bird once it leaves the colony. But on August 25, a single young tern was sitting on Beach 1 all by itself, happily preening away.

It had a band and, surprisingly, allowed a close enough approach that its leg could be photographed.

And there it was: #599.

It was Butterball. He had learned to fly!

It was a miracle. One that came about through the persistence of nature, the knowledge learned from 11 years of research, the dedication of park staff and researchers, and having natural spaces protected so species can find refuge, even in extreme weather years, and — of course — a little luck.

And if that luck holds, we hope to see Butterball back at Presqu’ile, raising his own little miracles on Gull Island in years to come.