Today’s post comes from Will Morin, Professor of Indigenous Studies at the University of Sudbury and Bruce Waters, former educator at the McLaughlin Planetarium and founder of the Killarney Provincial Park Observatory.

It’s time we learn the astronomical traditions of the diverse Indigenous cultures in the Americas.

For those of us who visit our more remote Ontario Parks, the view of the night sky is spectacular. Away from city lights, in the heart of the woodlands, the stars beckon, calling to you with their diamond-like splendor, challenging you to both admire and to understand them.

For thousands of years, our ancestors looked up at the night sky and successfully found a way to relate our souls and spirits to those ever-present glimmers in the darkness. At the end of the day, once all the chores had been completed, communities might gather at a local place to relate the day’s adventures and to pass on the lessons from one generation to the next.

Often, under a canopy of tens of thousands of stars, the ancients reflected deeply upon our eternal stories of gods, good times and bad, personal development, hope, and desire. The elders of these communities would retell origin stories or related cultural teachings and it should come as no surprise that those stories took their place amongst the patterns of stars above them, to be looked upon for all eternity.

So do we have more than one way to appreciate those star stories? The answer is, unequivocally, yes!

Cultures all over the world created their own constellations that reflected the stories that were important to them

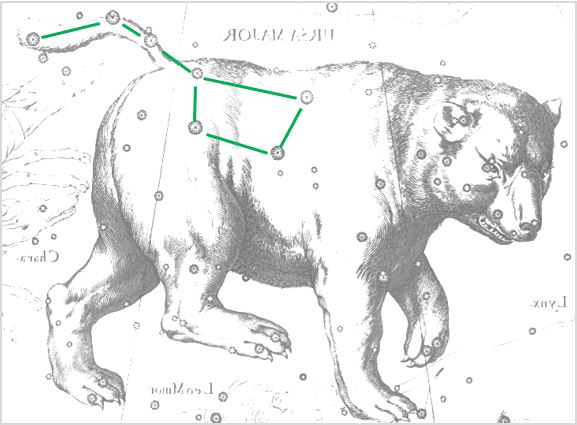

For example, the pattern known as the Big Dipper (three stars in a handle and four in a bowl, see below) is not an official Greek constellation, but a popular asterism that is part of a larger constellation known as the Great Bear or Ursa Major and is of ancient Greek origin.

The stars of the Big Dipper itself formed the African “Drinking Gourd,” the pattern of stars used by enslaved African Americans as they followed the Underground Railroad north.

There are 88 constellations that have become officially recognized around the world as a common reference. Most of these were created in ancient Babylon and incorporated into the knowledge of the ancient Greeks.

However, many cultures saw different patterns in the stars and gave them constellation names that were important to them. For example, the British saw the (Big Dipper) stars in the region of Ursa Major as the “Plough.” The Germans saw it as a “Wagon,” whereas Hindu people saw it as the “Septarshi,” with each star being one of the Seven Sages.

The people of the Middle East saw it as a funeral procession with the four stars of the Big Dipper’s bowl being the coffin, and the three stars of the handle being the pall bearers. The Chinese saw it as the seat of governmental power.

But what about the stories of those who lived in Ontario long before colonization: the Indigenous peoples?

Indigenous astronomy

To understand the star stories of the Indigenous peoples, we need to understand the geography of which we speak.

The Indigenous peoples of the woodlands of North America were and are the Anishinaabek, “people who were lowered [to Earth].” To the south of them were and are the Haudenosaunee, the “people of the long house” (often known as the Iroquois).

Both cultural groups shared many cultural elements, but were linguistically as different and diverse as the various European cultural groups. Each group had many different tribal and dialect groupings within the diverse geography around the Great Lakes and beyond in all directions.

- the Anishinaabek: Ojibway, Odawa, Potawatami around the Great Lakes, Algonquian to the eastern woodlands, and Cree to the north and west of the woodland

- the Haudenosaunee Confederacy: Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca and Tuscarora in many communities southeast of the Great Lakes

To understand these various tribes and their cultural diversity, we would have to experience the context in which they lived, including their geography and their relationship with the land, sky, and stars in each season.

Only from this vantage point can we understand the Indigenous culture or teachings, which is necessary before you can truly understand their stories. You can view this map to see your own region.

Star stories / Anangoonh Aadizokaanan

Like the European colonization of the land, so too was there an imposition of European star stories upon the already existing and rich stories of the Americas.

The existing Indigenous star stories were not just stories of “higher beings” and their often-amorous encounters, but were seen as part of an all-encompassing perspective of life and spirituality. Everything; the plants, animals, water, sky, and air were interwoven together in a complex web of life, understanding, and respect. The stars were a key part of that understanding narrative.

Anishinaabemowin, the language of the Anishinaabe, is a language of action and doing. That very language speaks of the science that’s out there in space, how something functions and its state of being. These ideas are all necessary to provide the context of Indigenous astronomy.

To the Anishinaabe, stars are animate because they move and have a spirit. Spirituality plays a big part in the universe because of both movement and energy. The Anishinaabek creator got his/her idea of creating the clans from the stars so everything starts with the stars. Learning to understand the stars is extremely important in aiding to predict both the weather and seasonal migration and other activities important in one’s life.

For example, in this part of the world, we experience the four seasons which, to many Indigenous, were marked by key events:

- Fall: Moose hunt, procuring necessary food and materials to last through the Winter

- Winter: storytelling and family time, reconnecting with one another

- Spring: breakup of the ice, seasonal flooding, and danger

- Summer: trapping and more leisure time

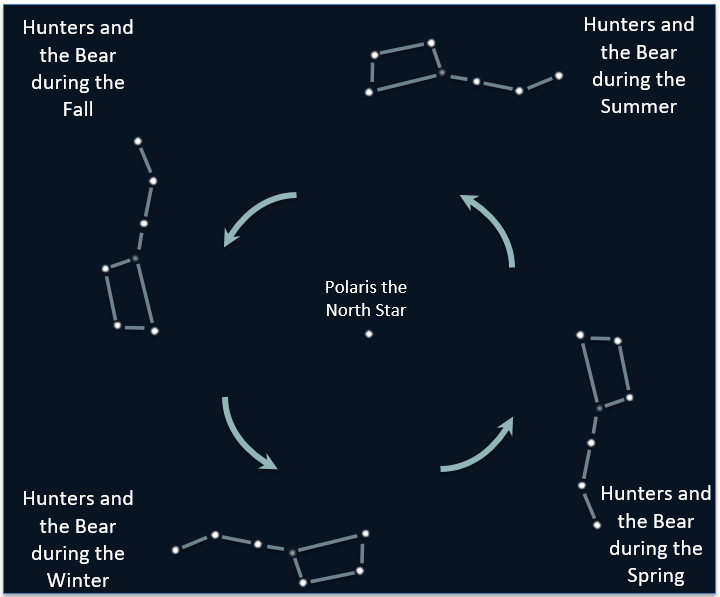

Significantly, the constellations of the Ojibwe sky are filled with stories that speak to and around the key themes that gain dominance during a particular season’s night sky. For example, in the Fall sky there is the large constellation of a Moose which becomes the focus of the night sky at that time of the year. Similarly, the Fall was also the time of the Moose hunt, in which many a person was involved in either the hunting or the harvesting of the Moose.

During the spring, there is the danger of falling through the breaking ice and being swept away. Often, at this time of the year, one can here creaking and groaning from under the ice. Not surprisingly, the constellation that represents this time of the year AND is well placed in the night sky is the water panther/lynx whose tail would thrash through the ice endangering the lives of many.

The Indigenous constellations provide the rich perspective of an integrated understanding of life and death that serve as a constant reminder as to how one should live their life. Other constellations provided additional stories that would serve to both further an understanding of the world as well as the providing of an important moral or way to live one’s life.

So what patterns of stars do the Indigenous people see near the Big Dipper?

The Haudenosaunee saw a bear within the Ursa Major region, but the bear itself was the bowl of the dipper and the “tail” was actually three hunter birds chasing the bear.

This story would seem to fit the pattern of stars better than the more well-known “Great Bear,” as the bear’s enormous tail (bears actually have very small tails) is eliminated altogether. It also helps to remind us of the leaves changing colour when the bear is low in the sky, or reminding us of the colouring of a robin.

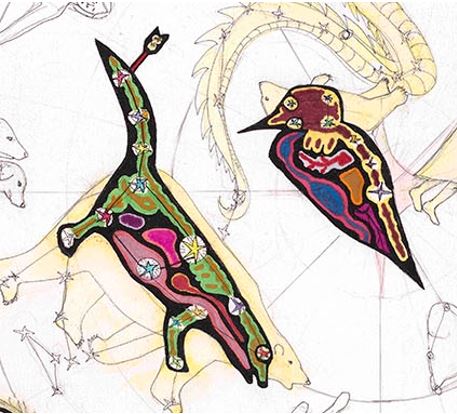

To the Anishinaabek people, this pattern of stars wasn’t a bear at all, but Ojiig the Fisher (pronounced, Oh-JEEG with an emphasis on the second syllable).

By being both strong and brave, Ojiig rescued the birds of summer, but at the cost of his own life (see the arrow in his tail in the picture above).

To commemorate his bravery, his image was placed amongst the stars for all to see. The stars within the region of the Little Bear was known to the Anishinaabek as Maang the Loon (pronounced, MAHng). Both Ojiig and Maang are beautiful constellations that fit the asterisms that they occupy, and are just a few of the constellations that are known to the Indigenous people.

Knowledge Keeping

According to the elders of various communities, there was a time long ago when every star had a name or connection to a constellation, each with its own stories to tell and lessons to learn. That information, and much more, has been all but lost to us in our present-day as a direct result of colonization and the disruption or outright banning of traditional knowledge sharing and practices.

Fortunately for us, there have been Knowledge Carriers and Elders who have passed down oral knowledge from generation to generation. Their star stories, as well as those found on birchbark scrolls, served as a memory tool to enable community leaders to continue the traditions and pass on the knowledge they knew.

In the last decade, amazing people and organizations such as Native Skywatchers, Wilfred Buck, the Star Guy, and Annete S. Lee, William P. Wilson and Carl Gawboy’s “Ojibwe Sky Star Map” have assembled this knowledge with extensive research, filling in the some of the lost information, and creating beautiful imagery to match the beauty of the stories themselves.

Connecting to the stories of those people who lived in Ontario long before colonization, the Indigenous peoples, is an act of shifting perspective and respect. We owe it to ourselves as well as to those who were here before us to learn these stories.

Will Morin is a Professor of Indigenous Studies at the University of Sudbury and a former interim-leader of the First Peoples National Party of Canada. He is an active artist and cultural advocate for First Nation’s rights and has worked tirelessly for over two decades to represent Indigenous peoples’ interests and perspectives to non-Indigenous Canadians.

Bruce Waters has been teaching astronomy to the public since 1980. He is a former educator at the McLaughlin Planetarium, founder of the Killarney Provincial Park Observatory, and science writer. He has authored the book A Camper’s Guide to the Universe and is a frequent contributor to the monthly Ontario Parks’ “Eyes on the Skies” blog.

The authors wish to thank the Elders and Knowledge Carriers at the Wiikwemkoong Heritage Organization for their review and feedback on this article most notably, Brian Peltier and Madeline Wemigwans.