Our “Forever protected” series shares why each and every one belongs in Ontario Parks. Our great system of protected areas is based upon a model of representation. In today’s post, Biologist Lauren Trute tells us Petawawa Terrace’s story.

For many families in the area, Petawawa Terrace Provincial Park is literally a park in their backyard.

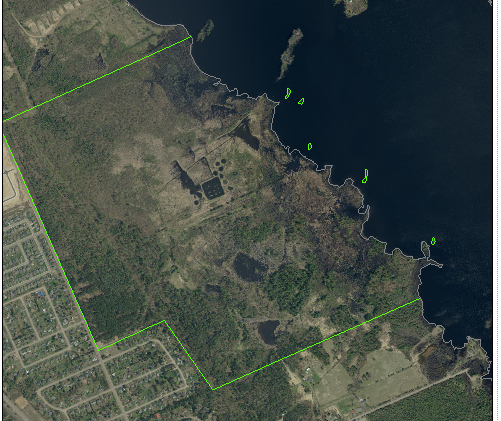

Unlike many provincial parks in Ontario, Petawawa Terrace is not pristine wilderness. Locally known as the “fish hatchery park,” the 215 ha park is located in the heart of the Town of Petawawa.

This little parcel of protected land belongs in the Ontario Parks system because it gives us a glimpse into Ontario’s history, and represents provincially significant ecosystems and species.

Petawawa Terrace’s representative heritage

With such rich natural landscapes, we sometimes forget that Ontario Parks is also committed to protecting our shared heritage.

Petawawa Terrace has been important to Ontario’s history of conservation. It was initially established as the Pembroke Crown Game Preserve in 1928. The Pembroke Trout Rearing Station operated between 1929-1994, one of the smallest and oldest in Ontario.

Elk transferred from Manitoba were raised in pens on the property for reintroduction in Ontario and Quebec from 1929 to 1945. The Petawawa Goose Sanctuary was established 1951.

Over its 70 years of operation, Pembroke Fish Culture Station supplied Lake and Brook Trout for stocking over 100 lakes in Pembroke, Bancroft, Carleton Place, Tweed and Napanee districts, as well as Algonquin Provincial Park. The station closed in 1995 as part of provincial fish culture restructuring.

In 1981, the adjacent Gutzman (Guntzman) Farm property was acquired to secure a water supply.

The buildings removed, but there has been some site restoration since that time.

Remnants of human habitat can also be found in the flora, with planted apple trees, day lilies and lilac shrubs making appearances in the landscape.

Right: Remnants of possible tobacco processing building

As part of the treaty negotiations currently underway, the Algonquins of Ontario have identified Petawawa Terrace Provincial Park as an area of historical and cultural significance within their territory.

Ontario and the Algonquins have agreed to work in collaboration in establishing management planning direction for this and other protected areas located within the treaty settlement area. The negotiating parties have agreed that ecological integrity will be the first priority in the management of parks and protected areas.

Petawawa Terrace’s representative ecosystems

Forgotten what “representative” ecosystem is? Refresh your memory here!

In 1983, the park was designated an Area of Natural and Scientific Interest (ANSI) for its provincially significant geological features (the terrace) and 14 provincially significant plants.

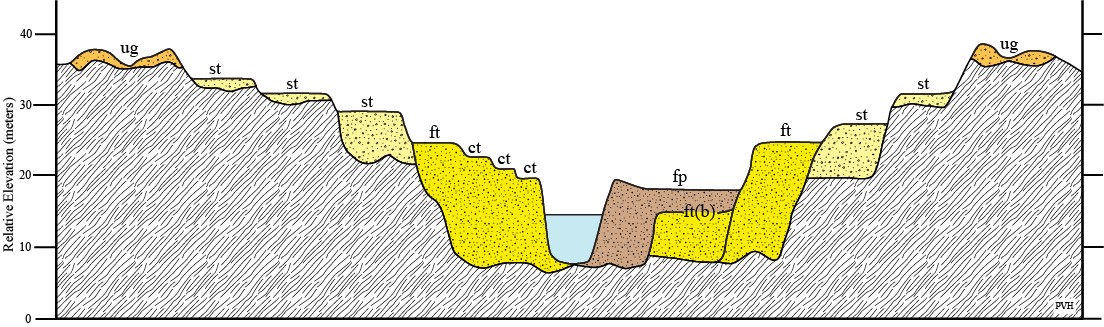

More than 10,000 years ago, at the end of the last Ice Age, a huge water body called the Champlain Sea flooded parts of Ontario and Quebec. As the water receded over several thousand years, terraces were worn into the landscape like geological footprints, giving us clues about our landscape’s history.

Not sure exactly how the terraces were formed?

Imagine a flooded basement.

Terraces along the Ottawa River are like the stairs to your flooded basement. The tread of the stair is the horizontal flat part of the terrace (also called a tread), and the riser of your stair is called the scarp.

Gradually, the water level goes down, step by step. But remember: floods are messy. When the water drains from your basement, it leaves behind all sorts of dirt and debris.

That’s exactly what happened in the Ottawa Valley.

As the water receded, the flowing water cut new steps (scarps) into the landscape, leaving behind new treads. And on each terrace (step), the waters left behind all sorts of glacial debris.

On Petawawa Terrace, we can find marine clay, left over from the ancient Champlain Sea. We also find sandy soils (a rare landscape in Ontario) and coldwater springs.

The terraces show us the history of post-glacial erosion, giving a hint of what has gone before, while also providing diverse habitat for wildlife.

The well-drained sandy soils on the upper terrace support an old Red Pine plantation, with occasional Jack Pine, Red Oak, Bur Oak and White Pine interspersed.

The lower area of the park has a diversity of habitats, including wetlands, field communities, deciduous lowlands and mixed woods.

Old field and open areas around the fish ponds are now filled with milkweed and wild red raspberry, making them havens for Monarch Butterflies and other pollinators.

Petawawa Terrace’s representative species

Just like we want to protect each type of ecosystem, we want to protect every species represented in an ecosystem, from towering pines to tiny beetles.

Petawawa Terrace is home to 14 provincially significant plants, including Spiny Quillwort, Small Purple Fringed Orchid, Tubercled Rochis, Coastal Jointweed, Goosefoot, Dropseed and Manna Grass.

White-tailed Deer and Black Bear are the two largest mammals in the park, and beaver, muskrat, mink, otter and raccoon can also be observed.

Over 70 bird species have been recorded, many of which breed on the site, including Baltimore Oriole, American Bittern, and Black-capped Chickadee.

Waterfowl are abundant in the spring and fall. Duck banding occurred regularly when the Fish Culture Station was in operation.

The park also protects species like Northern Leopard Frogs, American Toads, Snapping Turtles, Painted Turtles, several salamanders, and Monarch Butterflies.

In an increasing urbanized landscape, it’s easy to lose touch with the natural environment.

How awesome is it that we have parks like Petawawa Terrace right in our own backyard?