Welcome to the Ontario Parks “Eyes on the Skies” series. This “space” will cover a wide range of astronomy topics with a focus on what can be seen from the pristine skies found in our provincial parks.

The cold, crisp days of the New Year often reward us with fantastically beautiful nights, rich with bright stars and interesting sights.

Of the 17 brightest stars seen from Ontario, nine are visible during winter nights, and many interesting objects await the observer who is prepared to brave the cold.

Here are our astronomical highlights for January:

The sun

Many people believe that on the Winter Solstice (usually around December 21) we experience the earliest sunset and latest sunrise.

However, while the Winter Solstice marks the Sun’s lowest point in the sky at solar noon, and it does mark the day with the least amount of light, the earliest sunset always occurs earlier in the month. Similarly, the latest sunrise usually occurs in early January).

This year, for viewers at 45 degrees north, the latest sunrise occurs on January 5, when the sun will rise around 7:51 a.m. Coincidentally, the Earth just passed its closest point to the Sun, known as perihelion, on January 2.

Also note that our temperatures have everything to do with the amount of direct light falling on us rather than our distance to the sun; see our Equinox discussion for more information.

Keen to learn more about the solstices and equinoxes? See our March post here.

Sunrise and sunset times:

| January 1 | January 15 | January 30 | |

| Sunrise | 8:07 a.m. | 8:04 a.m. | 7:50 a.m. |

| Midday | 12:29 p.m. | 12:35 p.m. | 12:39 p.m. |

| Sunset | 4:51 p.m. | 5:06 p.m. | 5:29 p.m. |

The moon

The moon has long captivated observers of all ages. January’s lunar phases of the moon occur as follows:

The planets — Jupiter

Jupiter continues to be extremely well placed and is pretty much viewable all night long.

It is by far the brightest object in the night sky after the moon.

Meteor showers

January has one meteor shower – the Quadrantids – but it sure is a beaut!

Viewers who brave the cold can see at least 25 meteors/hour, but the shower can often display closer to 100 meteors/hour in dark skies.

The shower will peak between 1:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m., perfect timing as the first quarter moon will have nearly set by then.

The author of this blog (Bruce Waters) has seen this meteor shower from Mew Lake Campground in Algonquin Provincial Park, in -35ºC temperatures. Despite the cold, this meteor shower can warm the heart.

Featured constellations: Orion, Taurus, and Canis Major

For thousands of years, humans have looked up at the stars. The stars helped them try to understand their purpose, and the role stars play in our lives.

To help memorize the different stars, patterns of connect-the-dot figures were created by many different cultures. Today, we recognize 88 official patterns or “constellations” of stars.

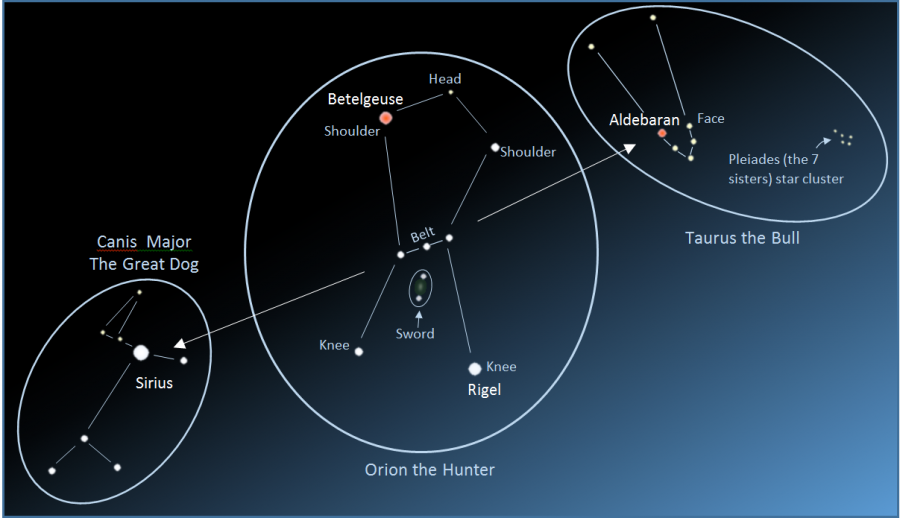

In this post we will explore three of those constellations: Orion the Hunter, Taurus the Bull, and Canis Major the Large Dog.

Orion is the great and boastful hunter of Greek Mythology.

Most people recognize the straight line of three stars making up the Belt of Orion.

The middle star of Orion’s belt (Alnilam) appears the same brightness as the other two belt stars. However, in reality, it is two times further away than both the left-most belt star Alnitak, and Betelgeuse, the red star marking one of Orion’s shoulders.

Underneath Orion’s belt is his sword. The middle object within the sword is a fuzzy, nebulous object that, when magnified, appears as a glowing gas cloud (easy to see in binoculars from provincial park skies).

Orion is accompanied by his hunting dogs (Canis Major and Canis Minor), and is doing battle against Taurus the Bull.

To find Canis Major, follow the belt of Orion down towards Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. A collection of medium bright stars flowing down and to the left marks out the body of the great dog.

If one follows the belt stars to the upper right, they will find the reddish star Aldebaran which, with a collection of faint stars, forms a “V.” The “V” represents the face of the bull (Aldebaran is the eye), and there are two stars above the face forming Taurus’ horns.

Towards the back of Taurus, one can find a cluster of stars known as the Pleiades. This cluster, also known as the “Seven Sisters,” is not a formal constellation. However, it is often mistaken for the little dipper.

Did you know…

The calendar has astronomical origins.

While the the constellations were, largely, created to help people remember significant star patterns, they have plenty of other uses. One of these is for the formation of the calendar.

For example, the ancient Egyptians watched out for the star Sopdet, which is known as Sirius in Canada today. They knew that each year, when they would spot Sopdet rising, the annual Nile floods would soon be upon them.

Click here to learn more about how the calendar came to be.

That completes January’s ode to the night skies

Check back each month as we highlight celestial events through the seasons, or click here to read more about astronomy in provincial parks.