Today’s post comes from Discovery and Marketing Specialist Dave Sproule.

Migrating birds are already arriving along the edges of Lake Ontario and Lake Erie, and many southern parks have birding events and festivals.

But for most of the migrants, these parks are just a rest stop after crossing those big stretches of water. Their destination may be much further north: the boreal forest.

What is “boreal” forest?

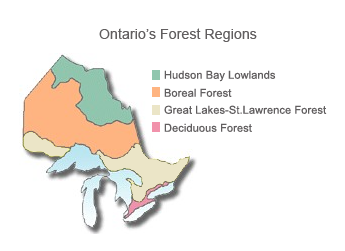

The boreal forest is vast. One of the largest ecosystems in the world, it encircles the globe’s northern reaches, from Europe to Russia to Canada. More than half of Ontario’s forest cover is boreal forest.

The boreal forest is vast. One of the largest ecosystems in the world, it encircles the globe’s northern reaches, from Europe to Russia to Canada. More than half of Ontario’s forest cover is boreal forest.

The word “boreal” means northern, so climate is a big factor in how this ecosystem functions and what species of plants and animals live in it. Long and cold winters mean that to survive year-round, you have to be tough.

For plants, it means that there are fewer species in the forest – only those adapted to living in cold climates can make it. The list of trees in our boreal forest is pretty short: Jack pine, poplar (like trembling aspen), white birch, black spruce, and white spruce are the main species.

The same goes for many animals – they have to be able to stand the cold winters, so they either hibernate (like turtles, frogs and bears), grow thick fur like lynx, fox and wolves, or develop other survival strategies.

However, many birds can escape the cold, flying south to where the climate is warm and food plentiful all year. Some stay put and live in the boreal year-round like Great Gray Owls, Boreal Chickadees, and Canada Jays, but the majority of birds migrate.

So if living in a tropical paradise is so great, why would birds fly hundreds or even thousands of kilometres to Northern Ontario?

One word: food.

The boreal forest is full of food. While the winters are cold and snowy, spring and summer have long days with lots of sun. Plants grow quickly, and as always, there is somebody waiting to eat those plants.

Caterpillars and other plant-eating insect larvae can be found in huge numbers, and birds are there to find them. During the breeding season, even species that are often thought of as seed-eaters need a tremendous amount of protein-packed insects to feed their growing young.

What types of birds live in the boreal forest?

Fun fact about birds in the boreal forest: many have acquired seemingly strange common names. This is often because they were named by observers far from their usual habitat. Palm Warbler, Magnolia Warbler, Connecticut Warbler, and Tennessee Warbler were all named as they were passing through on their migrations.

Warblers

Warblers are a family of songbirds that birders love. They include some of the most sought after species owing to their diversity, colour and beautiful songs (hence the name warbler).

Some, like the Yellow Warbler, breed throughout much of North America, but others breed almost exclusively in the boreal forest. Different species will be found in different habitat types.

Tennessee Warblers will be found nesting on the ground in relatively open mixed woods, while Palm Warblers are found near bogs and open wet coniferous forests. Others, like Bay-breasted Warblers, will be found nesting in relatively dense stands of conifers. Magnolia Warblers live high in the branches of pine and fir trees, and are rarely seen near the ground, but their songs are easily heard.

Warblers are “gleaners” meaning they carefully look for insects hiding under twigs and leaves. The Cape May Warbler is a spruce budworm specialist, checking the needles for the caterpillars that can, in some years, devastate fir trees.

Some familiar faces can also be found breeding in the boreal forest, as many birds from southern Ontario migrate to the boreal forest to take advantage of the numerous insects.

Sparrows

The iconic White-throated Sparrow known for its distinctive song “Sweet Canada, Canada, Canada,” will often be found at the boundary between open and forested areas which provide dense edge habitat, ideal for nesting.

Juncos may be familiar backyard feeder birds in winter, with their grey plumage and the white flashes of their tails, but as soon as spring comes, they vanish, headed to the boreal forest where the majority of them breed.

Lincoln’s Sparrow also depends on the boreal forest, but inhabit the wet edges, between treed margins and open water.

Thrushes

With the long hours of daylight, birds can forage longer, and with so many insects to eat, they can raise lots of young. Their territories can be quite close together because there is so much food available.

Last summer, within earshot of our campsite in Ivanhoe Lake Provincial Park, we heard three male Swainson’s Thrushes singing to warn each other, illustrating just how close their territories can be.

But how do I tell them apart?

It doesn’t take a birder to appreciate the diversity and abundance of birds in many northern parks.

You don’t need a lot of fancy gear to appreciate birds and nature. Just listening to them, and seeing them in their natural environment along a park trail is satisfying. If you want to know more about them though, like what family of birds they might be part of or even what species they are, a pair of binoculars is a handy piece of gear.

A field guide will help you identify the bird if you’ve gotten a good look: Sibley, National Geographic, Peterson are all good guide books and there are many more.

Finding out what others have seen in parks is only a click away

Most provincial parks have been identified as birding hotspots on eBird, a citizen science app that allows birders to record the species and locations of bird sightings.

And there are plenty of other apps for your iPod or phone. Sibley makes an eGuide that puts the field guide on your device. iBird is another guide. Merlin Bird ID asks you some questions about the bird you saw to help you make an ID. a number of other apps like birdJam use birdsong recordings and photos to help you ID what you’ve seen.

What could be better than going for a hike to look for and listen to birds?

It’s well-known that getting outside improves our health, both physical and mental, but researchers believe that listening to birds singing also has beneficial effects on our mental well-being.

Whether you just look and listen, or become a dedicated birder, a trip to our northern forests to experience Ontario Parks’ bird life will be a rewarding, and healthy one.